Technical Report Writing

CHAPTER

4 Data Gathering

A.

Summary

Data gathering is often more art than

science. In this Chapter we'll review some important but often overlooked data

sources, some unlikely data sources, the importance of the client or organization

as a source of data, and some pitfalls to avoid.

Also, the important concept of the "level

of detail" needed by each audience member will be addressed. As a final

reality check, always subject your data to common sense tests. Does this answer

really seem reasonable based on what you already know about the real world?

If it doesn't, look again!

B. Previous Reports/Literature Searches

The basic message here is "Don't

Re-invent The Wheel". Previous reports by your own organization and by

others are an important source of data and may save you days or months of work.

Always

find out if someone else has addressed the problem you are working on previously.

Get copies of earlier related reports. There are almost always some. Treat these

with caution though. They may contain errors or may be seriously out of date

or not precisely on target, but once you've satisfied yourself that some parts

of them provide reliable information, use them to the fullest extent possible.

One caveat = give credit where credit is due. Cite the previous reports fully

and thank their authors for doing some of your job for you. If you change the

data in any way, say so. It is unfair to others to change their data and subject

them to criticism for your possible errors.

C. Sources of Data

The data, i.e., the facts upon which

your report is based, will usually fall into one or more of the following categories:

·

Original Data

· Borrowed Data (Credit the Source)

·

Data provided by The Client

Original data from tests, measurements,

analyses, etc. are those facts you've developed under the most carefully controlled

and thought out conditions you can devise. Good empirical data results from

careful, meticulous work. Sloppiness will produce garbage and invite criticism.

You must be careful here however to balance time and cost against the ultimate

value of the data within the context of your technical problem. This is much

easier said than done, but ask yourself before you start how precise you need

to be. Would an error of 1 percent, 10 percent or even 100 percent make any

difference in the conclusions you draw from the data? Decide how much error

you can tolerate and still infer meaningful results.

Borrowed data is discussed above under

previous reports. If you have a choice, always use what appears to be the most

reliable data source for your report purposes. This is especially true when

you have several sources but the data from each differs somewhat. If the differences

are small, cite all the sources and average the data in some way. If the differences

are large, it is best to use the one source you feel the most confidence in

and explain in your report why you are making that choice. If you feel you must

include the other data sources, bury them in an appendix where hopefully no

one will find them.

Data provided by your client is often

problematical. You may at first feel that you have some "right" to

rely upon this data. Don't be fooled. Review this data as you would any other.

Is it complete? Is it accurate? Does it meet your reality checks?

For example, if your client tells you

that his water system provides 1 million gallons per day of water for each of

his 5,000 customers, do some simple math. This amounts to 200 gallons per person

per day. The national average is between 100 and 150. Numbers like these are

either in error or there must be some explanation for this high water use. Are

there major leaks in the system? Is there a large industrial water user such

as a cannery? Whatever the reason, you must find it and explain it and then

deal with it in your report.

In all data, including your own the

watchwords are:

·

Completeness

·

Accuracy

·

Reliability, i.e., reproducibility

·

Reasonableness (Reality Checking)

Some unlikely sources, which may at

first seem a joke to you, include the following commonly available books and

places:

The Public Library

City Hall

State and Federal Agencies

The Telephone Book

The Sears Roebuck Catalog

Hobby Clubs

Magazines in your field

Many writers of technical reports use these routinely for answers to sometimes

simple questions such as, what is the population of Arizona, or how much does

chain link fence cost, or how many sources of crushed rock might be available

to build this road?

Don't overlook these obvious sources.

The quality of the data is independent of the prestige of the source. A fact

is a fact.

D.

Inconsistent & Incomplete Data

When the data is inconsistent or incomplete

you need to decide early whether to try to salvage it, or dump it. Some very

crude data can be useful, if only for a first approximation, but measure the

time and effort you must spend to make sense out of data that doesn't at first

appear to make sense. If you decide to dump it, your early decision will help

you by possibly allowing you time to gather better data.

Incomplete data can often be "filled

in" by making reasonable assumptions about what happened during the periods

for which the data is missing. Be cautious here too. Remember that when you

do this you are, in effect, making up facts. Make absolutely certain that the

assumptions you make are reasonable and express them explicitly in your report.

Don't let somebody find out later that you made up data you didn't have. You

will appear foolish and possibly may be conceived as deceitful.

E. Levels of Detail and The Excess Perfection

Syndrome

Remember your audience? If not, this

is the place to be reminded of them. Each member of that audience has different

needs for the data in your report. Suppose you are writing a report on improvements

to the water system. The City Councilman may only need to know a few facts;

How much will it cost? When can it be done? How will it affect rates or taxes?

etc.

The Water Superintendent needs much

more detail. He may have a hundred questions such as; how much are annual chemical

costs going to have to increase ? What additional power requirements will your

plan entail ? Will additional staff be needed to operate the system ? Are added

tests required by the regulatory agency ?, etc.

There is one simple device for meeting

these widely varied needs for detail in your report.

Write the report moving from the general

to the specific.

As you discuss each topic in the report put the most important facts and conclusions first. These are, by definition, those facts and conclusions which every reader needs in order to understand your report and the problem it is written to solve. This topic will be revisited in Chapter 5, Report Organization, but it is mentioned here because it is one of the central ideas of good report writing.

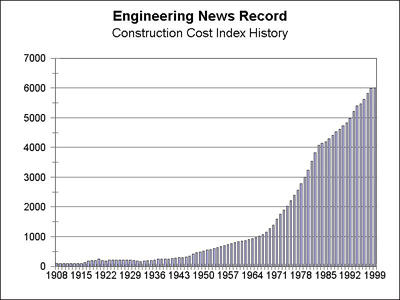

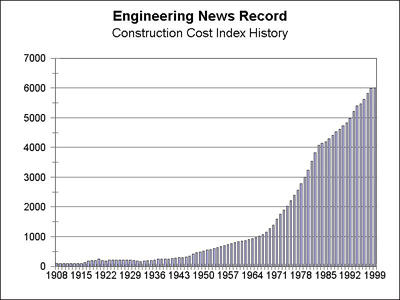

Figure 4-1

D.

Summary: Why You Must Clearly Define Both Problems

Unless, and until, you have defined both the technical problems to be solved and the rhetorical reason you are writing the report you can't answer such questions as; what am I doing, why am I doing this, how am I going to do this, and how will I convince others that what I have done is worthwhile ?

****

****